A terrific essay by Kenan Malik – je suis charlie? it’s a bit late.

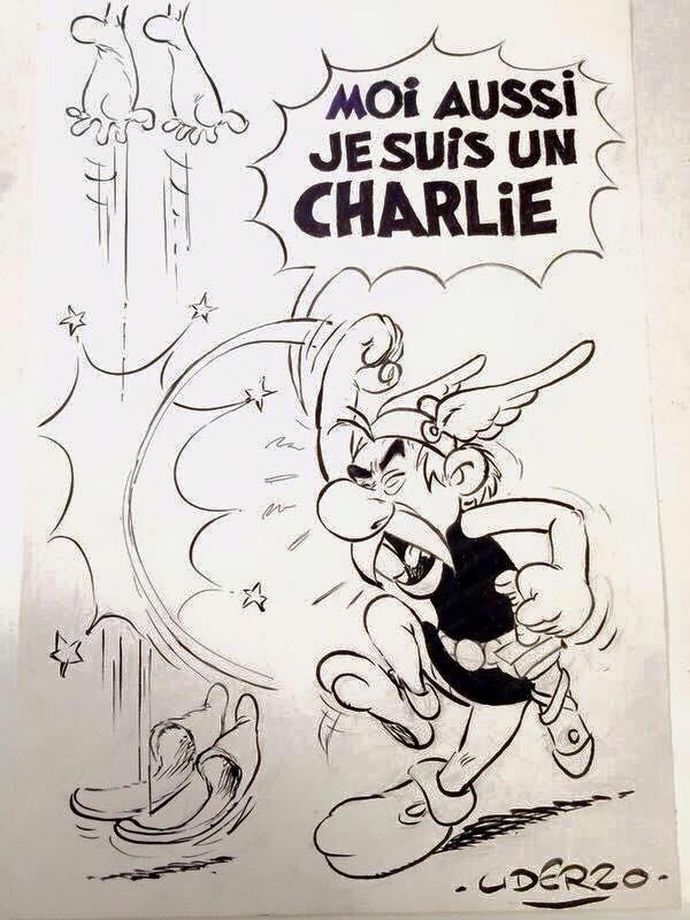

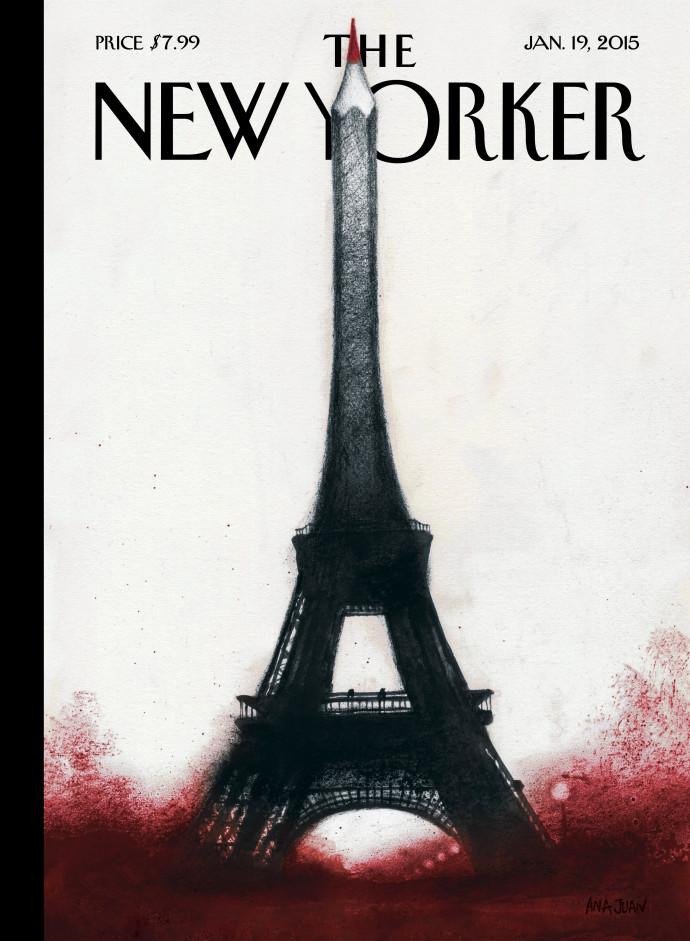

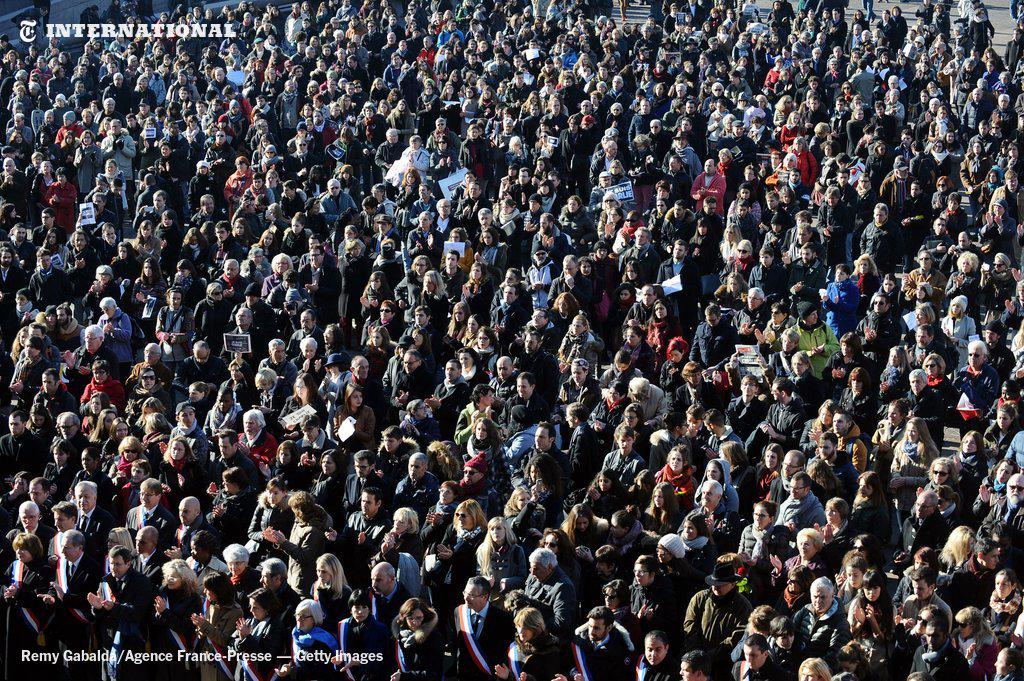

The expressions of solidarity with those slain in the attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices are impressive. They are also too late. Had journalists and artists and political activists taken a more robust view on free speech over the past 20 years then we may never have come to this.

Remember the fatwa on Rushdie? That’s when it started – people saying “wellllllllll maybe he really shouldn’t have…”

It’s partly fear, Kenan says, but not only that.

There has also developed over the past two decades a moral commitment to censorship, a belief that because we live in a plural society, so we must police public discourse about different cultures and beliefs, and constrain speech so as not to give offence.

In some ways, I do think we should do that (and I think Kenan would agree). I do think we should all refrain from shouting racist or sexist or homophobic epithets whenever we get irritated. I do think we should constrain our own speech in that sense. But discourse about beliefs? No.

So deep has this belief become embedded that even free speech activists have bought into it. Six years ago, Index on Censorship, one of the world’s foremost free speech organizations, published in its journal an interviewwith the Danish-American academic Jytte Klausen about her book on the Danish cartoon controversy. But it refused the then editor permission to publish any of the cartoons to illustrate the interview. I was at the time a board member of Index – but the only one who publicly objected. ‘In refusing to publish the cartoons’, I observed, ‘Index is not only helping strengthen the culture of censorship, it is also weakening its authority to challenge that culture’.

I remember that.

The irony is that those who most suffer from a culture of censorship are minority communities themselves. Any kind of social change or social progress necessarily means offending some deeply held sensibilities. ‘You can’t say that!’ is all too often the response of those in power to having their power challenged. To accept that certain things cannot be said is to accept that certain forms of power cannot be challenged. The right to ‘subject each others’ fundamental beliefs to criticism’ is the bedrock of an open, diverse society. Once we give up such a right in the name of ‘tolerance’ or ‘respect’, we constrain our ability to confront those in power, and therefore to challenge injustice.

Yet, hardly had news begun filtering out about the Charlie Hebdoshootings, than there were those suggesting that the magazine was a‘racist institution’ and that the cartoonists, if not deserving what they got, had nevertheless brought it on themselves through their incessant attacks on Islam. What is really racist is the idea only nice white liberals want to challenge religion or demolish its pretensions or can handle satire and ridicule. Those who claim that it is ‘racist’ or ‘Islamophobic’ to mock the Prophet Mohammad, appear to imagine, with the racists, that all Muslims are reactionaries. It is here that leftwing ‘anti-racism’ joins hands with rightwing anti-Muslim bigotry.

That second link is to Bill Donohue’s press release, which is fitting. If Bill Donohue is echoing you, you’ve gone terribly wrong somewhere.

What is called ‘offence to a community’ is more often than not actually a struggle within communities. There are hudreds of thousands, within Muslim communities in the West, and within Muslim-majority countries across the world, challenging religious-based reactionary ideas and policies and institutions; writers, cartoonists, political activists, daily putting their lives on the line in facing down blasphemy laws, standing up for equal rights and fighting for democratic freedoms; people like Pakistani cartoonist Sabir Nazar, the Bangladeshi writer Taslima Nasreen, exiled to India after death threats, or the Iranian blogger Soheil Arabi, sentenced to death last year for ‘insulting the Prophet’. What happened in the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris was viscerally shocking; but in the non-Western world, those who stand up for their rights face such threats every day.

They do. I know some of them; I’ve heard some of their stories.

What nurtures the reactionaries, both within Muslim communities and outside it, is the pusillanimity of many so-called liberals, their unwillingness to stand up for basic liberal principles, their readiness to betray the progressives within minority communities.

So don’t be that kind of liberal. Really don’t. Stand with the progressives, the Taslima Nasreens and Raif Badawis and Charlie Hebdos.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)