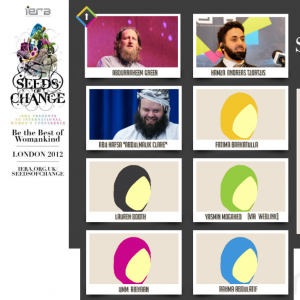

iERA has issued a press release with the heading

iERA Investigates Complaints about Seating Arrangements at the debate, “Islam or Atheism: Which Makes More Sense?”

It reports that UCL doesn’t want iERA doing any more talks at UCL, because of the gender segregation.

UCL’s reasoning is that they do not allow enforced segregation on any grounds at meetings held on campus and their assertion is that “attempts were made to enforce segregation at the meeting (sic).” iERA complied with the request from the University to cater for all preferences by having seating that was open for all attendees, male or female, and two sections to accommodate those that wished to adhere to their deeply held religious beliefs.

Ahhhhhh look how they word that, the tricksy buggers. They make it look as if the university requested two sections to accommodate those that wished to adhere to their deeply held religious beliefs. I don’t think the university did request that – although according to what Fiona McCallum told Chris Moos, they did say that would be “fine” – which was a big mistake.

We also adhered to UCL’s request to make sure that the respective areas were clearly marked and ushers were employed in order to facilitate the seating.

Did the university request that? How interesting if so. Reminiscent of signs saying “white entrance” and “colored entrance.”

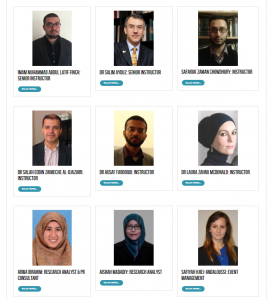

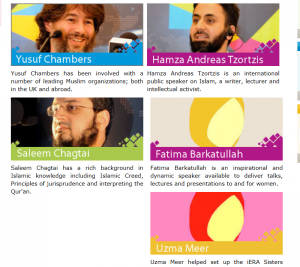

iERA is an inclusive organisation and its lecturers are the most popular on UK campuses.

The most popular on UK campuses? I don’t believe that for a second.

iERA aims to bring different people together and with this goal seeks to accommodate varying needs. It is a common practice amongst Muslim communities across the UK, based across different schools of thought, to have separate seating arrangements for men and women out of modesty.

So everywhere they go in the UK, Muslim women demand that men evacuate the premises out of modesty? I don’t believe that for a second either.

In light of this iERA accommodated various preferences on the matter, whether religious or non-religious, by having areas to suit everyone. iERA has a responsibility under the Equalities Act 2010 to accommodate any reasonable adjustment to enable all members of society fair access of opportunity including those of religious orthodoxy.

Bullshit. iERA does not have a responsibility under the Equalities Act 2010 to force its own horrible theocratic rules about shoving women to the back on everyone else. On the contrary. It has a responsibility not to.

UCL claims to have received some complaints from attendees who say they were asked to sit in a different section to what they chose. In a formal meeting we asked UCL to furnish us with details of those attendees and they were not forthcoming. We then offered UCL our entire guest list to check the email addresses to that of the complainants, they declined this also.

Ah. iERA tried to get UCL to identify the people who complained. Oddly enough, UCL didn’t feel obliged to help iERA bully the people who objected to gender segregation on university property. Good for UCL.

iERA is an organisation committed to constructive dialogue between people of all faiths and none, people of all colours, creeds or sexual orientation so it takes any complaints very seriously. In the absence of co-operation from UCL (although we are hoping that this will no longer will be the case), iERA is conducting an internal investigation with immediate effect. If we find there were any failures on implementing the agreed guidelines on the day, we will be the first to admit this and we will apologise for not honouring our word to UCL, our attendees as well as the general public. This is in accordance with the ordinance from Almighty God who states in the Quran, the final testament to mankind:

“You who believe, uphold justice and bear witness to God, even if it is against yourselves, your parents, or your close relatives. Whether the person is rich or poor, God can best take care of both. Refrain from following your own desire, so that you can act justly– if you distort or neglect justice, God is fully aware of what you do.” [Surah An-Nisa, Verse 135]

Oh fuck off.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

I just died of lulz. I’ll be resurrected in 3 days’ time.